Ogregores—organizations that demonstrate collective agency—are all around us but are hard to grasp because they are not human, even though their most important parts are people. I will explore some analogies to get a handle on them, starting with ancient gods and ending with sci-fi hive minds. (This post won’t explore the stories associated with the various analogues and what they might say about ogregores.)

Summary

This post explores analogies for understanding ogregores—powerful group entities with their own agendas that are composed of people, technology, and processes. Ogregores are defined by two criteria: They are “catnets” (communities where all members share some category and are tightly networked) that demonstrate collective agency (they have boundaries, act in unified ways, represent their environment, pursue goals, interact with their environment, and adapt).

It explores five analogues for ogregores:

- Ancient Gods: While gods mirror ogregores in their autonomy, power, mystery, and relationship with humans through intermediaries, this analogy is limited by gods’ supernatural nature, anthropomorphism, lack of technological integration, and simplistic creation stories. The analogy is useful for illustrating ogregores’ mysteriousness and ubiquity, and the rivalry between them. It helps conceptualize how people relate to entities that transcend individual human scale, for example, how ogregores inspire devotion.

- Egregores: These occult “group thought forms” parallel ogregores in their emergence from collective human participation, the importance of symbols, and feedback between an entity and its members. However, their supernatural/psychic nature contrasts with ogregores’ material socio-technical reality. The analogy is particularly useful for understanding the non-material dimensions of ogregores, such as shared values and organizational identity. This is the weakest analogy.

- Golems: While these animated clay beings illustrate artificial creation and potential unpredictability, the analogy is severely limited due to golems’ simplicity, magical creation, singular purpose, and lack of distributed complexity. It works best as a cautionary tale about the risks of creating systems that exceed their creators’ intentions.

- Piloted Partnerships: Animal-handler pairs and anime mecha-pilot teams demonstrate specialization, mutual shaping, and emergent capabilities, but fail to capture ogregores’ scale, complexity, distributed nature, and longevity. The analogy is useful for exploring leadership dynamics and the interplay between human and technological components in ogregores.

- Sci-fi Hive Minds: These collective intelligences (like Star Trek’s Borg) most closely match ogregores in their emergent agency, distributed cognition, human-technology integration, specialized roles, and persistence. However, the analogy exaggerates member integration, underestimates individual autonomy, and over-emphasizes malevolence. Despite these limitations, this analogy is the most accurate, especially for understanding highly integrated, tech-intensive ogregores.

The document concludes with a comprehensive framework for evaluating analogies, finding sci-fi hive minds the strongest conceptual match, followed by egregores and piloted partnerships, with ancient gods and golems scoring poorly as analogies for understanding ogregores.

Introduction

Ogregore recap

Ogregores are potent group entities: organized assemblages of people, technology, and processes with their own agendas that may differ from that of their members. The parts are tightly integrated and interdependent. I have discussed them in various posts over the years, e.g. October 2021, February 2022, November 2022, December 2022, December 2023, March 2024, and June 2024.

Examples of ogregores include bureaucracies, cities, conspiracy theory networks, corporations, countries and nations, criminal organizations, fandoms, government agencies, industries and industry associations, multi-level marketing organizations, nations, religious movements and institutions, scientific disciplines, social movements, sports teams and professional sports leagues, standard-setting and other international bodies, and subcultures.

Criteria

Ogregores are not just any human group. I require them to meet two criteria: being a Harrison White’s catnet, and collective agency:

- Catnet. An ogregore’s constituent people share at least one characteristic (category), and every member has two-way social ties with at least one other member (network).

- Collective agency. Ogregores are collectives that meet these conditions for agency:

1. They have sufficiently clear boundaries that one can distinguish between them and their environment. The boundaries can be fuzzy, just as they are with individual people—is my microbiome part of me or not?

2. They act in a unified way despite having distinguishable components that are agents in their own right.

3. They can form internal representations of their environment, i.e., beliefs.

4. Goals and intentions. These purposes can differ from those of some or all their constituent people.

5. They interact with their environment to meet their goals, influencing and being influenced by it.

6. Ogregores adapt to changes in their environment, sometimes in ways not foreseen by their human creators and/or managers.

Collective agency depends on a group’s structure and organizing rules. For example, one may not need group agency to explain many actions of ruthlessly centralized organization where one person makes all the decisions. I suspect that very small organizations are not ogregores (pace List and Pettit), but I do not have a numerical threshold.

All ogregores exhibit collective agency, but not all collective social action is attributable to an ogregore. Examples of non-ogregore collective action include market manias and some consumer boycotts.

Attributes

Artificiality. Ogregores are made by people who set up governance rules (which may or may not be formal and explicit) and establish procedural and technological means of coordination.

Emergence. Ogregores arise from the interaction of their components, exhibiting properties beyond those of their individual parts. They can do things that their constituents cannot do individually, like mount an insurrection or make a movie. Agency is a weakly emergent property (Wikipedia/emergence). While it might be possible to explain the behavior in terms of constituent people, it might be impracticable. Even where disaggregated explanations are possible, collective agency can be a productive explanatory tool. List and Pettit (2006) argue that it can arise even for group agents as small as three people.

Persistence. Ogregores maintain their identity (e.g., their purposes and ability to act) even though their constituents may change as people join and leave, processes evolve, and technologies change. (Cf. DeLanda (2006 : 36): “… a large organization may be said to be the relevant actor in the explanation of an interorganizational process if a substitution of the people occupying specific roles in its authority structure leaves the organizational policies and its daily routines intact.”)

Nesting and overlap. Since people can be members of multiple social structures at the same time, ogregores can overlap. For example, the IETF and W3C are distinct organizations but some people are members of both; corporations are usually smaller than countries, but multi-national corporations can span multiple countries (e.g., Unilever, which has headquarters in the UK and the Netherlands, and is listed on multiple stock exchanges); a technology industry like social media can have enough coherence to act as a single ogregore even though it consists of divisions inside various corporations (e.g., Instagram in Meta, YouTube in Alphabet, TikTok in ByteDance).

Amorality. Ogregores like companies and states are usually not treated as moral agents. Corporations and bureaucracies are sometimes portrayed as good or (more often) evil, but that’s more an assessment of their impact than their moral standing. They are seldom taken to have a conscience or ethical judgment, although the humans directing them certainly do. Some ogregores (e.g., NGOs) may be perceived as morally driven, and others (or even the same ones) can exhibit harmful behaviors, such as child abuse, environmental degradation, worker exploitation, or encouraging addiction.

One can summarize ogregores in a schematic:

Many ogregores such as corporations “legal persons.” A corporation is an individual or group of people, e.g. an association or company, that that has been authorized by the state to act as a single entity and is recognized as such in law for certain purposes (Wikipedia/corporation). According to Wikipedia/legal person, “In law, a legal person is any person or legal entity that can do the things a human person is usually able to do in law – such as enter into contracts, sue and be sued, own property, and so on.” A legal person does not have all the powers of person, however. For example, it doesn’t have bodily rights; it can’t be imprisoned; it can’t vote or hold public office; and it can’t claim benefits meant for human welfare like pensions and unemployment or medical benefits.

However, ogregores are more than the legal concept of bodies corporate. I define them to include tools and processes, not just people. They are both human collectives and entities with a distinct identity of their own. Ogregores also do not have to be legal persons if they meet the criteria of catnets and collective agency. The legal concept, however, helps to frame a corporate ogregore as neither the individual(s) directing its actions nor the collective corporate culture of its employees.

Analogues for ogregores

I’ll discuss the following ogregore analogues:

- Ancient gods: The deities of ancient pantheons like Mesopotamian, Greek and Norse mythology. They are supernatural beings that act in the material world.

- Egregores: Autonomous psychic entities composed of, and influencing, the thoughts of a group of people. They are non-physical but can affect the physical world.

- Golems: Anthropomorphic, powerful beings in Jewish folklore that are created by magically animating inanimate matter, usually clay or mud.

- Piloted partnerships: Assemblages consisting of a person and another entity, often a working animal, like an archer on horseback or a police officer and a K9. The mecha in anime are partnerships of giant robots and human riders.

- Sci-fi hive minds: Multiple minds linked into a single collective consciousness or intelligence.

(I use “analogy” to refer to a comparison and “analogue” to refer to the thing an ogregore is being compared to.)

All these models for ogregores meet the following criteria, at least to some extent. Ogregores meet all of them. Some ogregore attributes like artificiality and emergence are not listed here since they do not apply to all the analogues.

- Agency. They all meet common criteria, listed above, like (1) distinguishability from their environment (i.e., boundaries, which need not be completely sharp); (2) acting in a unified, autonomous way in spite of diversity in their constituent parts; (3) having internal representations of their environment; (4) forming plans, goals, or intentions; (5) interacting with their environment in service of meeting their goals; (6) adapting in the face of obstacles or change in their environment. They can exceed the control of their creators and members, behaving in unintended, unplanned, unanticipated, or surprising ways.

- Amorality. They resist simple moral categorization. Their moral agency and accountability are debated because they are not human beings. It is usually taken that they are neither good nor evil but merely pursue their goals.

- Durability. They can persist over lengthy periods., and the composite analogues endure longer than the lifetime of their constituent parts—that is, they continue to function in the same way even when parts are replaced. Egregores and hive minds, for example, can outlive their original creators and human members.

- Physical effects. The entities can all affect the material world.

- Scale. They are larger and more powerful than an individual human being, sometimes much larger. I don’t have a sharp lower bound for the minimum number of people in an ogregore since other factors like inter-connectedness also play a role in collective behavior. However, all well-connected organizations of more than 10,000 people are probably ogregores.

Not analogues

I do not consider the following to be viable analogies:

- A single person is not large enough scale.

- Ideologies and social systems like capitalism, socialism, or liberalism are certainly large scale, but they do not have discernible boundaries. They function as the environment within which ogregores operate.

- Markets and economies, including phenomena like the fossil-fuel economy—dynamic, decentralized systems where goods, services, and information are exchanged—do not have sharp enough boundaries. These, again, are ogregore environments not ogregores themselves.

- Social patterns like patriarchy and other systemic discrimination can be powerful and pervasive, but do not have discernible boundaries. They are processes rather than objects.

- I exclude institutions as analogues or synonyms for ogregores because, following a common definition, an institution is “a humanly devised structure of rules and norms that shape and constrain social behavior” rather than a social object (Wikipedia/institution). Ogregores include rules and norms but also contain people and tools and are bounded entities. For more detail, see my post “Why say orgregore?”

- While one can use ecosystems to model collections of ogregores, an ecosystem on its own doesn’t have sufficient agency to qualify as an ogregore (pace Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis).

- Social imaginaries are too large scale and too abstract. Wikipedia/imaginary (sociology) defines an imaginary as “the set of values, institutions, laws, and symbols through which people imagine their social whole.” They resemble institutions in their abstraction but are oriented to understanding society rather than structuring behavior. They are like, but larger than, corporate culture, which I reject as an analogy for the same reason.

- Jungian archetypes have a mythological character that reminds one of powerful meta-human entities like ogregores, but they are best seen as models of psychological forces that drive individual people. I have tried to make connections between corporations and archetypes (e.g., my post “Mythical entrepreneurs”) but I now think that this is probably unwarranted anthropomorphism.

- Current artificial intelligence systems don’t have sufficient independent agency to qualify as ogregores (for all the talk about “agentic AI”). However, they simulate human intelligence and decision-making, and AI assemblages could qualify as an analogue—but are not considered here.

Not treated in this discussion

I am going to ignore the question of consciousness. Ogregore behavior exhibits intention and emergence that could be taken to indicate sentience (feeling states that the entity associates with itself) or even consciousness (there is something that it is “like” to be that entity). I have speculated that ogregores might be conscious (“Scious organizations”), but this post is agnostic about that. If one is worried about being pounced by a tiger in a dark forest, only its perceptions and motivations matter, not its sentience. That said, some of the analogies imply consciousness. Ancient gods are humanlike and presumably are conscious. Egregores are often described as having consciousness or intention in a direct sense. Philosopher Eric Schwitzgebel uses imaginary hive minds to speculate that entities like the United States is conscious (see below).

I’m also not going to treat two other important concepts, juridical persons, and bodies politic.

Juridical (i.e., non-human legal) persons are legal entities that can do the things a human person is usually able to do in law, such as enter into contracts, sue, and be sued, and own property. I am still wrestling with its ontological status. As a legal concept it is completely immaterial, but when instantiated as a body corporate like a corporation or government agency, it has all the makings of an ogregore. At this point I’m inclined to think that the firm is a more useful concept than a juridical person—and a firm just is a kind of ogregore, not an analogue. (Firms can be, but don’t have to be, juridical persons.)

A body politic is a group of people collectively organized under a single governing authority, viewed metaphorically as a living body, a unified entity. Its members function as interdependent parts of an imaginary body (Wikipedia/body politic). It is a metaphor for a particular class of ogregores: states. I leave it aside here because it is an unfamiliar concept to most people, and thus less helpful in an analogy.

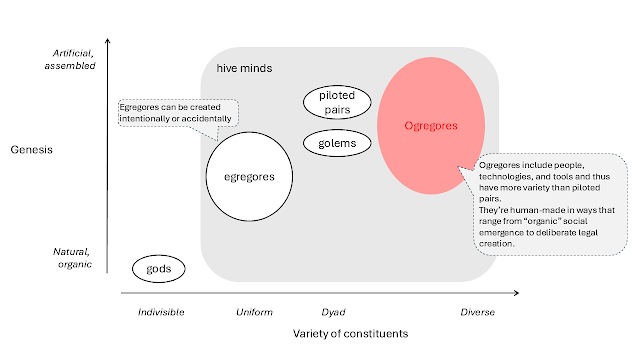

Mapping the analogues

One can distinguish between these ogregore analogues by mapping them against various dimensions.

- Materiality. This dimension ranges from the metaphysical/supernatural (e.g., gods) to material/physical (e.g., piloted pairs). Since egregores arise out of groups of people but have spiritual aspects, they shift away from the purely supernatural.

- Ogregores are physical.

- Multiplicity. The number of constituent components (not their variety; that’s the next dimension) in an assemblage. It ranges from one for gods to billions for hive minds like the Borg in Star Trek. I treat golems as unitary since they are an animate body.

- Ogregores have a large multiplicity, given their large number of human members, artefacts, and processes.

- Variety of constituents. This counts the number of distinct kinds of things making up an assemblage—not the total number, which is their multiplicity. Gods are indivisible. An egregore consists of its astral body as well as the people that nourish it. Piloted partnerships are dyads of people and animals/robots, and golems are dyads of matter and animating magic. Hive minds range widely, from the uniform (e.g., a single-species superorganism like Vernor Vinge’s tines, see below) to diverse (e.g., technologies and various species in the Borg).

- Ogregores have relatively large variety, consisting of people, many kinds of technology and process.

- Genesis. This ranges from entities that are naturally occurring like gods and superorganisms (with a variety of meanings of “natural”) to artificially assembled things. Entities that arise largely organically like bodies politic and egregores are less artificial than golems, juridical persons, piloted pairs, and hive minds. Ogregores have a range of originations, some spontaneous like social movements and others artificial like companies.

- Ogregore are artificial. They’re human-made in ways that range from “organic” social emergence to deliberate legal creation.

- Fictional/factual. This is a personal judgment made from my Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Developed-country (aka WEIRD) perspective. Gods, golems, egregores, and sci-fi hive minds are fictional in this account; juridical persons are legal fictions, and bodies politic are a social imaginary. Biological piloted pairs are factual and the mecha in anime are fictional.

- Ogregores are factual.

- Power. Gods, especially omnipotent ones, are extremely potent. Individual biological piloted pairs are weak compared to the other entities; however, mecha-pilot partnerships are quite powerful, more so than golems.

- Ogregores are moderately to very powerful (companies to nations, respectively) but not as potent as ancient gods.

I’ll work through the ogregore analogues in roughly increasing materiality, as shown by the dotted line in this chart that plots materiality against multiplicity:

Here are the analogues plotted against the other dimensions:

The Analogues Analyzed

We will now explore each of the analogies in more depth. After each discussion there will be an inventory of ways in which the analogy works, and ways it falls short. Many of the success/failure topics recur and will be indicated by green/red bold italics (thus/thus). The common topics, which are described in more detail at the end of this article, are as follows.

Common strengths across analogies

- Autonomy & unpredictability

- Ecosystems & relationships

- Emergence

- Fusion of tangible & intangible

- Human participation

- Specialization & integration

- Symbols & narratives/language

- Persistence beyond components

- Varied genesis

Weaknesses of several analogies

- Anthropomorphism

- Centralized control

- Fixed goals

- Fictional or supernatural

- No tech

- One-off creation

- Scale

- Scope of agency

- Simplicity

- Spatially localized

After looking at each analogy in turn, I’ll offer a checklist of attributes that work well to assess the suitability of an analogy and summarize the result in tabular form.

Ancient gods

Ancient pantheons could serve as frameworks for understanding distributed power systems that transcend human scale—like modern ogregores. I’m assuming that ancient polytheistic religions didn’t just personify natural forces but also created conceptual structures for understanding social power.

Ogregores like large corporations and nation-state organizations are powerful, pervasive, and mysterious.

- Power. Big Tech companies, for example, dominate the US stock market, with the Magnificent Seven (Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft, NVIDIA, and Tesla) making up 30% of the S&P 500’s value, up from 12% in 2015 (The Motley Fool). Their combined market cap in 2024 would have made them the second-largest country stock exchange in the world. The United States military has approximately 1.4 million active-duty personnel, and the Chinese Red Army has approximately 2.2 million.

- Ubiquity. Big Tech’s products and services are pervasive. As of early 2025, there were approximately 5.24 billion social media users worldwide, which represents 63.9% of the global population. Approximately 41% of Americans shop online every week, and nearly 40% of U.S. internet users engage with voice assistants like Alexa or Google Assistant for shopping.

- Mystery. Even Big Tech’s own engineers do not fully understand why the algorithms that drive social media and AI work in the way they do. Many government functions and bureaucracies are opaque; for example, the lack of transparency regarding who received COVID-19 Paycheck Protection Program led to public outcry. The Council of the European Union, whose deliberations are often closed to the public, is frequently criticized for its lack of transparency.

|

| Meme from Severance (KnowYourMeme) |

These are attributes that apply just as well to deities which have, by definition, god-like powers; are everywhere, and can appear anywhere; and demonstrate inscrutable motives and capricious behavior. They made alliances and engaged in feuds, like the squabbles of Zeus and Hera, and the Greek gods picking sides in the Trojan War.

Here are some examples from Roman and Norse mythology to motivate the analogy.

Mars, the Roman god of war, symbolized not just individual valor but, as the Empire grew, the disciplined and institutionalized military that was integral to Rome’s identity and power (Wikipedia/Mars). He embodied martial virtues such as discipline, honor, and courage, essential traits for Roman soldiers and was associated with the ideals of duty and loyalty to the Roman state. The later Mars was not chaotic and destructive like the Greek god Ares but was the image of military bureaucracy. In his Ab Urbe Condita, Livy chronicles Rome’s military campaigns and often references Mars in relation to the army’s successes and failures. In Parallel Lives, Plutarch discusses Roman generals (e.g., Marcellus) and their relationship with Mars, illustrating how the god’s persona influenced military leadership. Military formations, such as the testudo, were not just tactical but also embodied the collective spirit of Mars’s warriors. Mars became part of the Roman state’s identity, symbolizing the power and authority of Rome.

The Norse god Odin was associated with rulership. He was self-serving and subject to cosmic necessity. For example, he allowed the best warriors to lose their battles and their lives so that they could go to Vallhalla, strengthening his army for the decisive battle of Ragnarök. He was cunning and treacherous, for example, deceiving the giant Baugi, brother of Suttungr who controlled the mead of poetry, and seducing Gunnlöd, Suttungr’s daughter, to steal it. This is reminiscent of the Realpolitik that states engage in. The trickster god Loki reminds me of corporate deceptions (see, e.g., my ogregore stories Wezl’s Ghosts and MoeV Unmasked), on the one hand, and the social benefits they bring (cf. his role in obtaining the treasures of the gods), on the other. Both Odin and Loki were shapeshifters, which evokes the ways ogregores readily shift their political and business alliances (e.g., on DEI in the second Trump administration).

Tricksters, like tech ogregores, often have a complex relationship with power. Both Loki and Prometheus, another trickster associated with innovation, had close but fraught relations with the ruling gods, Odin and Zeus, respectively. Loki was Odin’s blood brother, and Prometheus, while tricking Zeus, also knew the secret of which amorous relationship could lead to Zeus’s downfall. This echoes the way in which states and tech entrepreneurs are both dependent on, and distrustful of, each other. Just as Zeus punished , states often regulate or try to constrain tech companies when their power becomes too great.

Avatars. Gods manifested through avatars and incarnations to interact with humans. Similarly, ogregores interact through human representatives - CEOs, spokespersons, brand ambassadors - who embody organizational values and are both distinct from, and part of, the organization itself.

Sacrifice. Ancient religions centered on sacrifice: giving something valuable in return for divine favor. Modern organizations similarly require exchanges: consumers sacrifice privacy to social media companies for free entertainment; employees sacrifice autonomy to corporations for wages; professionals sacrifice personal time and work-life balance to their employers in return for career advancement. Rituals in ancient religions can be likened to modern consumer behaviors. Engaging with ogregores—whether through voting in elections, participating in social media, providing free product reviews, membership of loyalty programs, buying branded merchandize, or “Black Friday” shopping—sustains their power in much the same way.

|

| A schematic representation of ancient gods |

Compared to ogregore attributes

- Agency. Gods function as individual agents with personal desires. They differ from ogregores in that ogregores—while meeting criteria for agency like boundaries, intentions, adaptability—function through emergent, collective action of their parts. Gods frequency act in unexpected ways.

- Amorality. God are not bound by human ethical rules. However, many pantheistic traditions linked deities to moral attributes, like Thor being associated with protection and justice, Krishna being the embodiment of compassion and wisdom, and Hanuman exemplifying devotion and selfless service. Other gods could be vengeful or destructive, like Poseidon causing storms and Kali destroying worlds.

- Durability. Gods are often, but not always, depicted as immortal.

- Physical effects. Gods intervene in the material world.

- Scale. Gods are more powerful than humans.

Ways the analogy between ogregores and ancient gods works well

Strengths shared with other analogies

- Autonomy & unpredictability. Both act of their own impulse, and their behavior can be unexpected.

- Ecosystems & relationships. Both exist within networks of peer entities with unstable relationships of competition and cooperation.

- Fusion of tangible & intangible. Ancient religious frameworks acknowledged both the tangible and intangible aspects of divine power, with physical temples and priesthoods alongside invisible spiritual influence. This mirrors the dual nature of ogregores as both material structures (buildings, employees, technologies) and immaterial forces (organizational origin stories, corporate cultures, brand identities).

- Human participation. Both rely on human engagement and have exchange relationships with people.

Other strengths of the ancient gods analogy

- Fluctuation and demise. The power of gods can rise and fall, as in the gods of city states in Mesopotamia. Both gods and ogregores can “die,” in the case of mortal gods in various traditions like the Norse, Hindu, and Mesoamerican. In some religions, like Norse mythology, gods can die. In the ancient Mediterranean religions, gods are local, often associated with particular cities, in the same way that governments and companies are grounded in specific localities.

- Mystery. Both gods and ogregores are at least partially incomprehensible to outsiders.

- Ubiquity. Both permeate daily life and exert influence across wide territories.

- Specialization. In both cases, individual entities develop expertise and influence within particular spheres. The analogy with ogregores works particularly well for gods in pantheistic religions where their many functions, from governance and warfare to fertility and intoxication, correspond with the many kinds of ogregores in the world. Just as gods have specific domains (war, wisdom, love), ogregores typically focus on specific industries (IT, energy, pharmaceuticals). Both entities can cover several functions: Athena represented both wisdom and war strategy, and Meta is buying undersea cables. In polytheistic religions, gods often interacted as part of a larger pantheon, balancing power and influence. This mirrors the ecosystem of ogregores, where governments, corporations, NGOs, and other entities coexist, compete, and collaborate.

- Alliances and rivalries. Both engage in competition and collaboration.

- Hierarchy. Both have webs of power relations among them, with some entities more dominant than others. Pantheons had pecking orders, and ogregores can have complex, hierarchical interrelationships, such as the online advertising ecology with a few dominant companies (Google, Meta, Amazon) and numerous smaller companies specializing in specific niches like local advertising, data analytics, and affiliate marketing.

- Human intermediaries. Both rely on human agents who both embody and remain distinct from the greater entity.

- Origin myths. Both have narratives that legitimize their position, trace their genealogies, and explain their character.

- Geography. Both maintain geographical anchors while projecting power broadly. Many ancient gods are localized in specific places.

Ways the ancient gods analogy falls short

Weaknesses shared with other analogies

- Anthropomorphism. While gods are explicitly anthropomorphized with human forms and emotions, ogregores are not consistently treated as if they were people.

- Fictional or supernatural. Gods are supernatural beings that exist outside natural law while ogregores arise from human activity and are rooted in material and technological systems.

- One-off creation. Gods are usually portrayed as primordial or created by elder deities, while ogregores are deliberately created by humans for specific purposes.

- Simplicity. Divinities are unified entities, and their capabilities don’t arise through the combination of parts. Gods are typically portrayed with coherent personalities and motivations, while ogregores often contain internal contradictions and competing agendas.

Other weaknesses of the ancient gods analogy

- Otherness. Gods are recognized as entities fundamentally different from humans, while ogregores are often conceptualized as extensions of human activity despite their emergent nature.

- Direct intervention. Gods can directly intervene in human affairs through miracles or manifestations, while ogregores act through human agents and technological mechanisms.

- Worship. Gods are worshipped as a central aspect of their relationship with humans. They were deeply embedded in cultural and religious traditions. While ogregores are the subject of compliance, adulation, or hatred, they are rarely truly worshiped and though influential, lack the sacred dimensions associated with deities.

- Source of Authority. Gods derive their authority from divine nature, while ogregores derive their authority from legal frameworks, economic power, or social contracts.

- Unaccountability. Gods are beyond human accountability but ogregores are subject to regulation, public opinion, and legal constraints.

- Reciprocity. Gods were often seen as benevolent or vengeful, rewarding or punishing human individuals or groups. Ogregores do not exhibit intentional reciprocity; their actions are shaped by structural conditions rather than personal favor or retribution.

Summary

Ancient gods resemble ogregores in their autonomy, power, origin myths, unpredictability, influence on human lives, and reliance on human intermediaries. Extending the analogy to include trickster figures, ritual exchanges, and pantheon ecosystems strengthens the comparison, providing insights into how ogregores function as modern “forces” shaping human life.

The analogy is particularly useful for illustrating ogregores’ mysteriousness, ubiquity, and their rivalry and cooperation with similar entities. It helps conceptualize how people relate to entities that transcend individual human scale, for example, how ogregores inspire devotion.

The analogy is limited because ancient gods are supernatural, anthropomorphized beings with divine origins, whereas ogregores are socio-technical constructs that emerge through human activity. Ogregores also lack the sacredness, direct intervention, and worship associated with gods. The analogy risks overemphasizing intentionality and coherence while underemphasizing the distributed, emergent nature of ogregore behavior.

I suspect the comparison between gods and ogregores more than metaphorical: it reflects deep structural similarities in how humans conceptualize and relate to powerful, complex entities that exceed individual human scale.

Egregores

Egregores are the concept that inspired the term “ogregore” (along with the word organization).

An egregore is an autonomous psychic entity that is composed of, and influences, the thoughts of a group of people (Wiktionary/egregore). It is non-physical but can affect the physical world. Theosophists define it as a “group thought-form” (Theosophy.wiki/egregore). Thought-forms are entities with “tenacity, coherence, and life” which exist on non-physical planes like the mental and astral planes (Theosophy.wiki/thought-forms). Another definition holds that “Any symbolic pattern that has served as a focus for human emotion and energy will build up an egregore of its own over time, and the more energy that is put into such a pattern, the more potent the egregore that will form around it. The gods and goddesses of every religion, past and present, are at the centers of vast egregore charged with specific kinds of power.” (John Michael Greer, Inside a Magical Lodge, 1998, quoted by Theosophy.wiki/egregore.)

The term “egregore” (sometimes “egregor”) comes from the Greek word “egrḗgoroi” (ἐγρήγοροι), meaning “watchers” or “those who are awake.” It appears in the First Book of Enoch, a pre-Christian Jewish apocalyptic text, where it refers to angelic beings. starting in the 19th century, various esoteric traditions adopted the term. The meaning in occult circles seems unrelated to that in I Enoch; I suspect a connection via the 16th century occultist John Dee’s “Enochian magic” which was picked up by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in the late 19th century. The concept is still current, even outside occult circles—cf. online groups practicing tulpamancy, the intentional creation of “tulpas,” which are thought-forms that practitioners believe can develop a degree of autonomy and personality (r/Tulpas).

Various writers use the term in diverse ways and there isn’t a single, uncontested definition. An egregore, in many of the conceptualizations I’ve seen, is a non-material entity that arises in a psychic plane but is dependent on (supervenes over) the material bodies of a group of people. It is an artificial being, generated by devotion, either intentionally or unintentionally (Theosophy.wiki/thought-forms). It is strengthened by conscious attention, ritual practices, symbols, and emotional investment. Human hierarchies also seem to be prerequisite in some conceptions. Egregores influence the thoughts and behaviors of the group while simultaneously being shaped by them. Commonly cited examples include a family, a club, a political party, a religious community, a social or political movement, a country or state, a benign or evil deity (Theosophy.wiki/egregore, Stavish).

As they develop, egregores may gain increasing autonomy from their creators, potentially surviving even after the original group dissolves, giving them a life span longer than a human’s.

Compared to ogregore attributes

- Agency. An egregore is an autonomous entity with the power to act on the physical plane (Theosophy.wiki/thought-forms). The egregore a human being affiliates with can become more powerful and consuming than the person intended.

- Amorality. Egregores can be good or (more often) evil in human estimation.

- Physical effects. Thought-forms, and thus egregores, can appear as apparitions or objects created by the power of the mind, cf. tulpas in Tibetan Buddhism (Theosophy.wiki). Tulpas have astral and mental bodies as well as physical ones (the material bodies of people who belong to the particular egregore). An egregore is the sum total of all these elements (Stavish quoting Mouni Sadhu).

- Durability. Egregores and hive minds, for example, can outlive their original creators and human members.

- Scale. The scale of an egregore depends on the number of its human adherents, and so can range widely, but it is typically more powerful than an individual person.

Ways the analogy between ogregores and egregores works well

Strengths shared with other analogies

- Autonomy and unpredictability. Both have agency that can exceed the control of their creators or members. Both develop increasing independence from their creators over time.

- Emergence. Both egregores and ogregores are emergent entities that arise from the collective actions, thoughts, and interactions of groups.

- Fusion of tangible and intangible. Egregores have both physical (the members’ bodies) and non-physical aspects (thought-forms or astral bodies). Similarly, ogregores combine tangible elements (people, infrastructure) with intangible ones (protocols, goals, and culture).

- Human participation. Both egregores and ogregores depend on the participation of their constituent humans, without which they cease to exist. Both rely on human engagement and grow in strength with strong affiliations of their members.

- Persistence beyond components. Both maintain continuity despite loss of, or turnover in, individual components.

- Varied genesis. Both can be created intentionally or may emerge without planning.

Other strengths of theegregore analogy

- Fluctuation and demise. Both can grow stronger or weaker over time and may cease to exist. They are shaped by internal and external forces.

- Composites. Both are coherent composite entities that are composed of distinct individuals.

- Belief. People’s membership in an egregore (as in bodies politic and ogregores) is partly defined by acceptance of certain beliefs or narratives.

- Feedback. Both influence the thoughts and behaviors of the people who constitute and sustain them, and in turn are influenced by them.

- Symbols. Both embody shared goals and values. Both are strengthened through symbols, rituals, and shared narratives.

- Common explananda. Both concepts can be invoked to discuss social institutions like corporations, religious organizations, or countries. However, there are instances that fall outside the overlap: families are too small to be ogregores.

Ways the egregore analogy falls short

Weaknesses shared with other analogies

- Anthropomorphism. Egregores are often anthropomorphized as beings with distinct personalities or intentions. While ogregores can exhibit agency, their “intentions” are emergent and non-biological and anthropomorphism is unlikely to be a good guide to intuition.

- Fictional or supernatural. Egregores are rooted in occult or esoteric traditions and are often described as psychic entities existing on astral planes. Ogregores have physical infrastructure (e.g., buildings, communication networks, supply chains) and analyzed using materialist frameworks that focus on sociological, technological, and organizational dynamics. Egregores are often described as having supernatural powers whereas ogregores operate entirely within the physical and social realms, relying on human actions and technological systems. Ogregores can be empirically observed through their material effects and structures; being able to perceive egregores seems to require the acceptance of metaphysical frameworks.

Other weaknesses of the egregore analogy

- Scope of Integration. Egregores are made of people’s thoughts and emotions; ogregores integrate not only human behaviors, but physical artifacts as well.

|

| A schematic representation of egregores |

Summary

The term “ogregore” melds the occult and everyday, taking the esoteric concept of collectively generated entities and grounding it in observable organizational structures while acknowledging their sometimes monstrous or inhuman qualities.

Psychic egregores closely match ogregores in the emergence of collective agency from individual components, reliance on human participation, persistence beyond individual members, feedback between the entity and its constituent parts, importance of symbols, and the combination of tangible/intangible dimensions. While the occult framework may not be true in a scientific sense, it captures important psychological and social dynamics that more materialist frameworks can overlook.

The non-materiality and mystical aspects of egregores make this analogy less applicable to ogregores’ tangible, socio-technical nature.

Egregores are particularly useful for understanding the non-material dimensions of ogregores – the shared beliefs, values, and identities that animate organizations beyond their material structures. They could also shed light on the balance between intentional creation and spontaneous emergence.

Golems

Golems are anthropomorphic, living beings in Jewish folklore created from inanimate matter, usually clay or mud (Wikipedia/golem). They are artificial beings not unlike robots—stories about both emerged from Central Bohemia. (The modern concept of robots was popularized by the Czech writer Karel Čapek, who introduced the term “robot” in his 1920 play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots); cf. Rose Eveleth.) In some stories, rabbis activate golems through the magical use of Hebrew alphabet, such as the word emet, truth. The lack souls.

|

| The golem of Prague (image creator not known) |

Golems serve as mirrors of human creative potential and its limitations. They highlight the precariousness of creating artificial agents. Their creators must maintain control through precise instructions, lest the golem become a threat.

|

| Schematic representation of a golem: material + magic |

Compared to ogregore attributes

- Agency. Golems are given tasks by their creators and can execute them without supervision. However, golems are typically depicted as simple and rigid rule-followers, while ogregores are dynamic systems that can adapt and evolve. Golems follow instructions and act semi-autonomously but often develop unintended behaviors—sometimes destructive—beyond their creator’s intent. Golems can fight back, e.g. one of them scarring the Gaon Eliyahu Ba’al Shem when he tried to deactivate it. A version of the “Golem of Prague” narrative has it falling in love and becoming a violent monster when rejected. The emergence of agency in ogregores when people, tools, and processes coalesce may seem mysterious, just like a golem animated from clay through ritual processes.

- Amorality. The golem’s morality is often ambiguous. It is neither inherently good nor evil but follows its instructions with rigid logic.

- Durability. Golems typically last as long as the magical conditions or rituals that animate them remain intact. They’re often created for a specific task like performing labor or defeating an enemy and are de-animated once the need passes. The duration or “life span” of a golem typically depends on the specific mythology or story in which it appears and can be as short as days or weeks. This contrasts sharply with ogregores which are much more long-lived.

- Physical effects. Golems act in the world.

- Scale. In early Jewish folklore, golems are typically depicted as human-sized or slightly larger. In modern media such as tabletop role-playing games, golems can range from human-sized to immense, towering figures several stories high.

Ways the analogy between ogregores and golems works well

Strengths shared with other analogies

- Autonomy & unpredictability. Both have agency that can exceed the control of their creators. There is a risk that it will not act the way its creator intended.

- Fusion of tangible & intangible. Both golems and ogregores are fusions of the material (clay for golems; people and technologies for ogregores) and symbolic (letters or words; values, norms, algorithms). Both represent transformation from distinct components to entities with agency.

- Symbols & narratives/language. Both are formed using ritual, language, and symbols.

- Artificiality. Both are artificial beings.

Ways the golem analogy falls short

Weaknesses shared with other analogies

- Scope of agency. Golem’s actions are limited and physical.

- Simplicity. Golems are simple beings with limited internal complexity while ogregores possess complex internal structures, often with competing elements.

Other weaknesses of the golem analogy

- Genesis. Golems are always deliberately created by specific creators, but ogregores may emerge in an undirected way without intentional design or a single creator (e.g., movements). Golems are created at a specific moment while ogregores may emerge gradually.

- Inanimate substrate. Golems are made of inanimate matter with no agency or awareness while ogregores consist of conscious humans with their own agency and awareness.

- Magic. Golems are physical beings created through mystical means while ogregores emerge through social processes and interactions.

- Not distributed. Golems are single anthropomorphic beings with unified bodies but ogregores are distributed collective entities comprised of many individuals; ogregores’ anthropomorphism is limited to how we talk about them (e.g., “the corporation wants,” “the organization decided”).

- Not emergent. The capabilities of a golem are designed into it by virtue of its constituent parts.

- Not long-lived. As noted above, the duration or “lifespan” of a golem depends on the mythology or story in which it appears and can be as short as days or weeks.

- Not socio-technical. The golem analogy doesn’t capture the socio-technical nature of ogregores.

- Singular purpose. A golem is usually created with a singular purpose (e.g., to protect or serve). Ogregores often have multiple, evolving, and sometimes conflicting goals that arise from their complex structures.

Summary

Comparing ogregores with golems is the weakest of the analogies.

On the plus side, golems illustrate the artificial human construction, integration of language with tangible aspects, and potential unpredictability of ogregores. However, the analogy is limited due to its simplicity, singular and magical creation event, rigidity, and lack of distributed, emergent complexity.

The golem is most useful as a warning about the unintended consequences of creating powerful systems that can exceed their creators’ intentions, but it lacks the nuance to capture ogregores’ emergent and technological dimensions.

Piloted partnerships: Animal-handler and mecha-pilot pairs

One way to understand a centrally directed ogregore is as an animal with a human handler, such as an elephant and a mahout, an archer on horseback, a sniffer dog and a customs officer, or a falconer and hunting eagle. While the human is more intelligent and is responsible for planning and directing activities, the animal has abilities that the handler does not, like size, strength, speed, or keener senses. (I’m not saying that any CEOs consider their employees to be animals. Certainly not.) The combination of an animal and its handler can perform tasks that neither could do on their own. The animal’s unique abilities are analogs of the specialized capacities of an ogregore, such as its ability to harness collective human effort, manage vast data, or exert influence at scale.

|

| Scythian Archer (Pinterest) |

Livestock guardian dogs (LGDs) like sheepdogs are an interesting corner case (Wikipedia/livestock guardian dog). They have some independence in protecting flocks of sheep. However, their effectiveness is significantly influenced by the training and guidance they receive from their human handlers. LGDs are bred to guard livestock, and their ability to protect is largely instinctive. Their bodily constitution is not unlike an organization’s legal constitution: a set of guiding principles set up in the past that acts in the present. The puppy training of LDGs is vital for developing their protective behavior, and they require ongoing training and supervision, especially during their formative years.

|

| Chicken Jockey (A Minecraft Movie, Know Your Meme) |

The animal and handler form a Deleuze and Guattari assemblage (Wikipedia/assemblage). Each influences the other: the handler shapes the animal’s behavior through commands and training, while the animal’s reactions and needs shape the handler’s decisions and actions. One could also use Latour’s Actor-Network Theory (ANT) to analyze how handlers, animals, tools, and environments interact to produce specific behaviors. This approach emphasizes the distributed agency within the assemblage, which aligns with the emergent behavior of ogregores. Leaders, technologies, and external conditions all shape the ogregore’s actions, just as they shape the behavior of the animal-handler pair.

In addition to real-world partnerships, there is also a fascinating science fiction version of animals and handlers: the mechas–large, piloted mechanical constructs—in anime (r/anime). Mecha stories often grapple with the relationship between humanity and technology, which can shed light on our relationship with tech-intensive ogregores.

|

| EVA Unit 01 (Wallpaper Flare) |

The influential series Neon Genesis Evangelion explores psychological themes and the relationship between pilot and mecha which is particularly useful when thinking about the relationship between leaders and their organizations. The Evangelions (aka Evas) are giant, ensouled, biomechanical, humanoid mechas, cyborgs with both mechanical components and organic structures like eyes, skin, and internal organs (Wikipedia/Evangelion, EvaGeeks.org). As in other robot anime, they are piloted by children.

While the extent of Eva sentience is debatable, they are implied to have some degree of awareness and agency beyond just being piloted since they contain the souls of their pilots’ mothers (Reddit).

Andy Clark and David Chalmers’ theory of “extended cognition” and Edwin Hutchins’ work on “distributed cognition” provide theoretical tools for cognitive processes that encompass multiple brains, tools, and environmental structures. One could also explore Donna Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto” for ways in which human-technology hybrids challenge traditional boundaries and categories, relevant to understanding both mecha pilots and leaders of tech-integrated ogregores.

The concept of “commander’s intent” plays a crucial role in modern warfare by providing frameworks that enable centralized intelligence to guide distributed action while allowing for autonomy and adaptation among forces.

Both animal-handler pairs and mechas involve feedback loops, where the handler’s commands shape the system’s behavior and the system’s responses influence the handler’s decisions. In ogregores, similar feedback loops exist between leaders, organizational components, and external conditions. Similarly, mutual trust between ogregores and their leaders helps achieve goals.

These entities are so small (only two components) that one can question their collective agency. The joint entity probably doesn’t form internal representations of its environment, thus failing one of the agency criteria—though arguably the least important one. The directed part (animal or mecha) maintains its agency even when direct control from the human is interrupted. Here are examples from both real-life and sci-fi partnerships:

- Evangelions, particularly Unit-01, can act independently, going into a “berserker” mode where they operate without a pilot’s instructions or a clear external power source.

- In footnote 33 to her translation of Lucretius’ The Nature of Things, Book V, line 1340, (a depiction of war elephants going rogue when injured) A.E. Stallings writes:

Carthaginian mahouts were equipped with an iron spike to drive into the brain of an elephant if it was wounded, for a wounded elephant would run amok. There is a historical example of an elephant killing friends as well as foes found in Plutarch’s Life of Pyrrhus: “An elephant named Nicon, one of those which had advanced further into the city, was trying to find its rider who had been wounded and fallen off its back, and was battling against the tide of fugitives who were trying to escape. The beast crushed friend and foe together indiscriminately until, having found its master’s dead body, it lifted the corpse with its trunk, laid it across its tusks, and wheeling round in the frenzy of grief, turned back, trampling and killing all who stood in his path.” (Plutarch: The Age of Alexander, trans. Ian Scott-Kilvert, Penguin Classics, 1973, my quotation marks.)

Both examples parallel how ogregores can develop behaviors that diverge from the intentions of their leaders, highlighting the potential for ogregores to exhibit agency that is not entirely under human control.

|

| Schematic piloted partnerships |

Compared to ogregore attributes

- Agency. Piloted partnerships meet five of the six agency criteria: boundaries, unified action, goals, interaction, and adaptation. I doubt the joint entity forms internal representations of the environment, thus failing one criterion. Animals or mechas can go rogue when their pilots lose control. The Ghost in the Shell anime and manga examine how networked intelligence creates emergent properties beyond individual components, directly relevant to ogregore behavior.

- Amorality. Piloted partnerships are the most problematic in this respect, if one assumes that the human pilots have enough control of the pair to be held accountable for actions that bring benefit or harm.

- Durability. Piloted partnerships can outlive their original human members, as when a K9 is retired and their handler starts working with a new dog, or an elephant gets a new mahout. The lifespan is roughly limited to a human one, though, and this is a weakness of the analogy.

- Physical effects. Piloted pairs act in and on the physical world.

- Scale. Piloted partnerships, especially mechas, are larger and more powerful than an individual human being. However, biological pairs are not much more potent than humans, and so these analogues are a weak model for ogregores.

Ways the analogy between ogregores and piloted partnerships works well

Strengths shared with other analogies

- Autonomy & unpredictability. In both cases, there is a risk that the directed part will act unpredictably as far as the director is concerned, and thus that the combination will act in surprising ways.

- Emergence. In both cases, the components cooperate to achieve goals that neither could accomplish alone. Both demonstrate how integration creates emergent properties.

- Specialization & integration. Both involve functional specialization that creates system-level effectiveness—each side provides abilities that the other lacks. In both cases, the directing human delegates specific tasks to the directed part, trusting it to perform autonomously within certain bounds. Success in both kinds of system depends on skill, training, and alignment between the directing and directed parts. Both capture the mutual shaping and feedback loops between components. Both display intelligence that emerges from interaction between parts rather than being centralized.

Ways the piloted partnership analogy falls short

Weaknesses shared with other analogies

- Scale. There is a scale and relationship mismatch: piloted partnerships typically involve only two constituents whereas ogregores involve hundreds to millions of individuals, plus technologies. However, the combination of a mecha’s giant cyborg body with a human pilot is like a large organization that combines people and technology being helmed by a single manager.

- Simplicity. The analogy misses the internal political complexity and conflict of ogregores: piloted partnerships are cooperating (and sometimes conflicting) pairs while ogregores exhibit complex political dynamics, competing interests, conflicting goals, and factions. Ogregores involve intricate ethical and structural issues—such as governance, accountability, and systemic biases—that are not easily paralleled in the simpler dynamics of animal-handler or mecha-pilot relationships.

- Spatially localized. While they may be huge, piloted partnerships exist in one place and are not geographically distributed like ogregores.

Particular weaknesses of the piloted partnership analogy

- Commanded control. Piloted partnerships aren’t a good model for distributed or non-hierarchical organizations like cooperatives and movements. In piloted partnerships, there is a dominant controlling agent, the human handler/pilot; decentralized ogregores ones lack a single, centralized leader. However, piloted pairs are decent analogies for ogregores with powerful leaders.

- Intelligence hierarchy. All the human components in an ogregore are similarly intelligent, whereas there’s a clear intelligence hierarchy in most piloted partnerships. Similarly, all the humans in an ogregore have moral agency, unlike the animals and mechas in piloted partnerships.

- Limited unpredictability. While animals and machines can exhibit some unpredictability and even go beserk, their behavior is constrained by training or programming. On the other hand, ogregores are far less predictable and can evolve in unforeseen ways.

- Physical control. Piloted partnerships rely on direct physical control (reins, voice commands, neural links) while ogregores operate through complex social, cultural, and institutional mechanisms.

- Short lifespan. Ogregores can persist for generations, outlasting any human member, whereas the piloted partnerships are often formed and dissolved for specific missions and rarely exceed the lifetime of the human handler.

- Simple technology. While mechas introduce a technological dimension, the analogy does not fully capture the complexity of modern ogregores, which integrate advanced technologies like AI, logistics management, and social networks.

- Weak emergence. While a piloted pair may have capabilities that its components separately do not, this emergence is very weak since it can be easily explained by reduction to parts.

Summary

This analogy highlights the relationships between leaders and led, the emergent capabilities of combined components, and the role of specialization and interaction between parts. It captures the interdependence and amplification of abilities of leaders and led.

However, piloted partnerships are small and short-lived. They lack the internal complexity and complex internal dynamics of ogregores. They fail to capture ogregores’ distributed multi-agent structure, adaptability, and long-term persistence even as components change.

It works best as a simplified model of leadership dynamics, particularly for ogregores with powerful leaders or simple organizational structures. It is also useful for illustrating the functional integration and mutual reliance between leaders and led, and humans and technologies. It can illuminate bidirectional influence between leader and organization, communication protocols that bridge diverse types of intelligence, and the variety of integration from loose coupling to deep fusion.

Hive Minds

Hive minds are multiple minds linked into a single collective intelligence or consciousness. They are inspired by superorganisms like ant colonies or bee hives (Wikipedia/superorganism). Holobionts, assemblages consisting of a host and many other species living in or around it, may be relevant when thinking about corporations that accrete swarms of suppliers and contractors (Wikipedia/holobiont).

In this post, however, I'm going to explore sci-fi hive minds rather than real-world biological aggregations. One of the best-known is the Borg. These recurring antagonists in the Star Trek fictional universe are cyborgs linked in a hive mind or group mind called “The Collective” (Wikipedia/Borg, Fandom/Borg). Borg drones can share thoughts and perceptions.

The Borg Collective strives to assimilate technology and sufficiently advanced organisms. The idea of assimilation—adding the “biological and technological distinctiveness” of other species to their own—resonates with ogregores, which aggregate human, technological, and cultural components to form a larger, more powerful system.

In early episodes, the Borg did not have a hierarchical command structure. The Borg Queen was introduced in Star Trek: First Contact (1996) as an expression of the Borg Collective’s overall intelligence, not as a controller. This was contradicted in Star Trek: Voyager (1995–2001), where she is seen explicitly directing, commanding, and in one instance even overriding the Collective. The early “first among equals” Borg Queen corresponds to the perspective that CEOs are merely expressions of a corporate agenda. The domineering late Borg Queen corresponds to a CEO that determines the actions of a corporation.

This shift shows the power of anthropomorphism. The authors of The Computers of Star Trek (1999) are quoted in Wikipedia/Borg as saying, “It was a lot easier for viewers to focus on a villain rather than a hive-mind that made decisions based on the input of all its members.”

|

| The dreaded Borg (Photo: CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images) |

Sci-fi authors’ distaste of the Borg and other hive minds in sci-fi mirrors a widespread dislike of corporations in various groups. It plays on ideas about the loss of individuality when people become cogs in a corporate machine, and fears about corporations brutally absorbing smaller companies or ignoring local cultures. The Borg expresses the Star Trek ethos including suspicion of corporate greed, perhaps reflecting the 1960s counter-culture origin of the franchise. In this view, organizations often demand conformity and subsume individual agency into the collective goals of the entity—just as the Borg do.

This take on hive minds is not limited to Star Trek. The Science Fiction Encyclopedia (SFE) notes that “Most sf novels which imagine hivelike human societies find the idea repugnant. . . . Hive minds which can recruit or incorporate normal humans are regarded with particular dread.” This mirrors societal fears of losing individuality and becoming subsumed by larger entities—whether corporations, governments, or cults.

There are many examples of hive minds in Science Fiction (Wikipedia/group mind, SFE/hive minds), including:

- A single group mind uniting the entire human species (the “Eighteenth Men,” our current species being the “First Men”) in Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future (1930).

- The hive of variegated organisms living in an asteroid in Bruce Sterling’s “Swarm” (1982, collected in Schismatrix Plus, 2006). Simple, individual actions of the nanobots lead to sophisticated, emergent behaviors (Wikipedia/Swarm). The swarm can adapt to changes in its environment and learn from interactions, making it a dynamic and responsive entity—a hallmark of agency.

- The Formics (aka Buggers) in Ender’s Game (1985) by Orson Scott Card act as a hive mind coordinated by a queen (Fandom/Formics). This collective’s misunderstanding of humans as non-intelligent due to our non-hive mind structure reflects the challenges of inter-group communication, applicable to interactions between humans and ogregores, and ogregores of diverse types.

- In the video game series StarCraft (1998 onwards), the Overmind is a vast, collective consciousness that controls the Zerg species. It represents a hive mind, interconnected and far larger than any individual Zerg. However, while the Zerg are individual organisms, the Overmind is localized, often depicted as a large, pulsating mass with a distinct brain-like structure.

- Each “tine” in Vernor Vinge’s A Fire Upon the Deep (1992) is a small pack of dog-like creatures sharing a group consciousness (Wikipedia/Fire upon the Deep). Different members serve specialized functions like memory, processing, and communication. When members die, they can be replaced while maintaining continuity of the tine’s identity.

- The Flood in the Halo franchise (2001 onwards) is a parasitic alien lifeform that infects sentient beings, transforming them into various specialized forms to serve its collective purpose (Wikipedia/Flood (Halo), Halopedia/Flood). The Flood operates as a collective consciousness that becomes more sophisticated as it assimilates more sentient beings. The Flood also creates forms known as “key minds” to coordinate the Flood’s actions.

Myths and histories can feature hive mind-like entities. For example, the Greek concept of demos (the people as a collective political body) or the Roman idea of the res publica (public affair) reflect early attempts to conceptualize collective agency.

Hive minds also appear in philosophical thought experiments. Eric Schwitzgebel posits two hypothetical kinds of conscious being in the course of making the eponymous argument in “If materialism is true, the United States is probably conscious” (2015). Both Sirian supersquids and Antarean antheads are hive minds of a sort, with obvious analogies with distributed human organizations.

- Sirian supersquids live in the oceans of a planet orbiting Sirius. They have a central head and a thousand tentacles, and are as linguistic, artistic, and creative as human beings. They show all external signs of consciousness. A supersquid brain is distributed among nodes in its thousand tentacles, but its cognition is fully integrated. They can detach their limbs which remain in contact and cognitively integrated with each other using light signals.

- Antheads are animals living on a plant around Antares that look like woolly mammoths but act much like human beings, though their cognitive activity takes about ten times longer to execute than ours. Their heads and humps contain not neurons but rather ten million miniscule squirming insects (hence “antheads”). Ants come in many kinds and specialize in different tasks. Schwitzgebel explains that these creatures “are much-evolved descendants of Antarean ant colonies that evolved in symbiosis with a brainless, living hive.”

The internet has been described as a kind of hive mind, where billions of users contribute to a shared repository of knowledge and interaction (Orion Jones, James Sirois). Platforms like Wikipedia or social media networks are said to exhibit emergent behaviors and collective intelligence. However, I don’t consider the internet to be an ogregore since it doesn’t have a clear boundary. Wikipedia defined as its contributors probably isn’t one, either, because it fails the catnet criterion: while they share the characteristic of making contributions, there aren’t sufficiently strong 2-way social connections between them. Social media networks might be ogregores; interest-oriented groups on these networks, like subreddits, also probably qualify.

Cultures or social movements can function as hive minds, with shared values and collective goals driving the behavior of their members. For example, the civil rights movement or climate activism could be seen as ogregores with distributed leadership and emergent agency, although in specific cases the interpersonal connections might not be strong enough to ensure sufficient coherence.

|

| Schematic of hive mind |

Compared to ogregore attributes

- Agency. Hive minds like the Borg meet the six criteria for agency. Surprise is a necessary element in narratives like those of sci-fi hive minds.

- Amorality. It’s not clear whether entities like the Borg are moral agents, though their behavior is subject to moral disapproval.

- Durability. Hive minds live much longer than their constituents, just as bee hives and ant colonies outlive their constituents.

- Physical effects. In their fictional worlds, these entities have real effects.

- Scale. While some hive minds are smaller than ogregores (e.g., the six-unit tines in A Fire Upon the Deep), most are vast, consisting of planetary or galactic species-civilizations.

Ways the analogy between ogregores and hive minds works well

Strengths shared with other analogies

- Autonomy & unpredictability. Both have agency that can exceed the control of their creators or members.

- Emergence. Both demonstrate collective agency and behaviors that cannot be reduced to their individual parts; both demonstrate how integrated components can produce higher-order cognition.

- Persistence beyond components. Both maintain continuity despite loss of, or turnover in, individual components.

- Specialization & integration. Both feature collections of cognitively highly capable parts. Both have a mix of homogeneous and diverse elements, including classes of similar entities which have specific roles, expertise, and goals.

Other strengths of the hive mind analogy

- Anti-corporatism. Repugnance of hive minds in sci-fi corresponds to the distaste of large corporations that many people feel.

- Distributed processing. Both exhibit physically distributed cognition.

- Centralized or decentralized. Both can have decentralized or centralized control.

- Collective memory. Both create knowledge repositories transcending individual memory.

- Coordination. Both integrate diverse types of organisms or entities into a cohesive collective, achieving synchronized activity across numerous components.

- Ethical issues. Both raise ethical issues about autonomy, subjugation of the individual to the collective, and collective accountability.

- Governance. Hive queens match the role of an organizational leader, while egalitarian hive minds such as that in the Swarm resemble cooperatives

- Growth. Both grow by assimilating new members and technologies.

- Slow thinking. The connection speed between sub-parts can be quite slow, e.g., in both Antarean antheads and corporations.

- Technology. Both the Borg and ogregores fuse technology and people into a single entity.

Ways the hive mind analogy falls short

Weaknesses shared with other analogies

- Fictional or supernatural. Sci-fi hive minds like the Borg (not ant hills and bee hives, of course) are a literary fiction.

Other weaknesses of the hive mind analogy

- Biological communication. Hive minds typically involve mind-to-mind biological/neurological integration while ogregores integrate using communication technologies, cultural norms, and social systems.

- Coercion. Hive minds usually portray involuntary assimilation or biological determination whereas ogregores typically involve voluntary (though constrained) participation.

- Exclusivity. Hive minds generally demand exclusive membership in one collective whereas ogregores allow individuals to participate in multiple organizational entities simultaneously. Hive minds have clear boundaries between members and non-members while ogregores often have fuzzy boundaries with varying degrees of participation and influence.

- Loss of individuality. In many hive minds, e.g., the Borg, individuality is lost and individual autonomy is completely overridden. In ogregores, individuals retain some degree of autonomy and distinct identity.

- Malevolence. Hive minds in fiction are typically portrayed as inherently malevolent or oppressive. While ogregores can raise ethical concerns, they are not inherent evil and can have positive social impacts.

- Massive scale. The number of units in many hive minds, such as billions of Borg drones and the nodes in Schwitzgebel’s supersquids and antheads, are orders of magnitude larger than the number of people in even the largest organization.

- Quick consensus. Hive minds are often portrayed with instantaneous consensus decision-making, while ogregores feature complex deliberative processes, voting, hierarchies, and negotiations.

- Singular goals. Hive minds typically pursue a single, unified goal (e.g., the Borg’s quest for perfection). Ogregores often have multiple, sometimes conflicting goals that arise from their complex structures and diverse stakeholders.

- Uniqueness. There is only a single hive mind in the Star Trek universe, the Borg, in contrast with thousands of competing ogregores in our world.

Summary

The hive mind is the closest thing in my list to a metaphor (“an ogregore is a hive mind”) and not just an analogy (“an ogregore is like a hive mind”)—though this may just betray my bias that the hive mind is the best among the analogues we’re examining.

Hive minds align closely with ogregores in their emergent collective agency, distributed cognition, persistence, collective memory, specialized roles, and integration of humans and technology. The analogy with the Borg is particularly strong for large, technology-intensive ogregores.

However, the analogy is weakened by fictionality, coercive membership, singular goal orientation, malevolence, and exaggerated loss of individuality. Hive minds tend to have singular goals and some have a larger scale than most ogregores. The analogy overestimates the degree of integration in ogregores and underestimates the autonomy and identity of their human members. Hive minds don’t capture the nuanced cultural, technological, and ethical dimensions of ogregores.

The hive mind analogy is useful for understanding how collective intelligence emerges by integrating networked components and how organizational memory transcends individual participation. It is useful when discussing highly integrated socio-technical systems, and when exploring ethical tensions between collective and individual interests.

Comparison Framework

This section pulls together recurring strengths and weaknesses seen in the analysis. It synthesizes these attributes into a checklist that can be used to assess the quality of each of the analogies.

Common strengths and weaknesses of the analogies

The following attributes are in green/red, bold, italic text (thus/thus) in the comparisons above.

Common strengths of analogies

- Autonomy & unpredictability. Entity acts autonomously and can behave in unexpected ways, independent of creators’ intentions. Examples: ancient gods, egregores, golems, piloted partnerships, hive minds.

- Ecosystems & relationships. Entity operates within networks of other entities, engaging in competition, collaboration, and adaptation. Examples: ancient gods.

- Emergence. Entity arises from collective interaction, exhibiting properties beyond individual members. Examples: golems, egregores, piloted partnerships, hive minds.

- Fusion of tangible & intangible. Entity operates simultaneously in tangible and intangible ways. Examples: ancient gods, egregores, golems.

- Human participation. Entity requires human agents or intermediaries to function and maintain itself, or at least has exchange relationships with people. Examples: ancient gods, egregores.

- Specialization & integration. Entity combines sub-entities of different types with specialized roles into cohesive systems. Examples: piloted partnerships, hive minds.

- Symbols & narratives/language. Entity gains strength from shared symbols, rituals, and origin stories that unify their constituents. Examples: golems.

- Persistence beyond components. Entity maintains continuity despite turnover among individual parts. Examples: egregores, hive minds.

- Varied genesis. Entity can be created intentionally or may emerge without planning. Examples: egregores.

Ways analogies can fall short

- Anthropomorphism. Excessive humanization or overly simple personification that doesn’t fit ogregores’ complex, distributed, and non-human nature. Examples: ancient gods, egregores.

- Centralized control. Entities have singular centralized control, which does not capture the distributed nature of many ogregores. Examples: piloted partnerships.

- Fixed goals. Entities have singular, fixed purposes, whereas ogregores have evolving and sometimes conflicting goals. Examples: golems, hive minds.