Charles Fréger’s Yokainoshima: Island of Monsters and Phyllis Galembo’s Mexico Masks Rituals got me thinking about how people in different cultures represent the monstrous. Since Moderns don’t believe in ghosts and demons, so we demonize people. Non-humanoid monsters are relatively rare and examples, especially dire serpents, often live in the uncanny valley avoided by robot designers.

|

| Charles Fréger, Namahage |

Demonizing people

Of course, we do worry about non-human monsters, but they’re tied to “real” phenomena. Depending on one’s ideology, it could be Capitalism, Socialism, Big Government, and/or Greedy Corporations.

If we talk monsters, we must invoke the Jungian shadow. In Jung’s Man and his Symbols, Marie-Louise von Franz provides a quotation and commentary in a caption for an image of a wildly gesticulating Adolf Hitler:

“For over five years this man has been chasing around Europe like a madman in search of something he could set on fire unfortunately he again and again finds hirelings who open the gates of their country to this international incendiary.”

Rather than face our defects as revealed by the shadow, we project them onto others – for example onto our political enemies. . . . Above, Hitler during a speech; the quotation is his description of Churchill.

(Part 3, “The Process of Individuation,” Man and his Symbols, Dell Publishing Co, 1964, p. 181)

In this approach, we hold up as monsters that which we unconsciously feel to be monstrous in ourselves. Perhaps there’s a link to the way we become like our enemies – or perhaps we create enemies to be like us. For example, the 2024 Democratic campaign fell into fearmongering about the democracy-dooming prospect of another Donald Trump presidency – Trump, a man whose success is built on fearmongering; and a Democratic Party that did an end-run around primary voters who supported Joe Biden.

The practice in ancient Greek theater to put even historical characters behind masks appeals to me. It increases impact by providing some distance. I found Spitting Image, the satirical British TV puppet show, much more entertaining than SNL’s rather lame in-person impersonations (though in both cases, the monsters represent real people, not abstractions).

|

| "Boris Johnson" on Spitting Image |

|

| Charles Fréger, Akaoni |

|

| Charles Fréger, Aooni |

|

| Charles Fréger, KioniIt’s easy to be reminded of the Disney animation Inside Out (2015) in which the protagonist Riley |

Thinking about demons took me to political cartoons, and in particular, Joseph Keppler’s 1904 drawing in Puck magazine that depicts the Standard Oil Company as an octopus. The Evil Octopus was a trope: not only Standard Oil got this treatment but also Corporate Greed, the Aldrich Plan, and even England.

(To Do: Investigate images of corporate monsters.)

Non-humanoid monsters

Monsters that are people got me thinking about non-humanoid monsters in movies etc.

The obvious ones were Godzilla (and the kaiju genre in general) and the Angels in Neon Genesis Evangelion. The first few are anthropomorphic (Adam, Lilith, Sachiel) but then they get weirder, like the insectoid Shamsel, the blue octohedron Ramiel, and the aquatic Gagiel.

|

| The Angel "Shamsel" (Neon Genesis Evangelion) |

|

| The Angel "Ramiel" (Neon Genesis Evangelion) |

|

| The Angel "Gagiel" (Neon Genesis Evangelion) |

In science fiction, I thought of the Black Cloud in Fred Hoyle’s eponymous book, though admittedly the cloud is just the antagonist and not (as it turns out) a monster.

Non-humanoid monsters in mythology include Fenrir and Jormungandr in the Norse tradition. Serpents are big in Indo-European demonology, cf. Typhon and medieval European dragons generally.

I couldn’t think of any non-humanoid monster protagonists in US movies. GPT40 suggested Clover (from Cloverfield), the shark in Jaws, and the Rancor (from Star Wars: Return of the Jedi). Claude-3.5-Sonnet suggested Frank the rabbit from Donnie Darko. That led me to The Giant Behemoth (1959 British-American science fiction action horror film), and the alien in Alien. Many of them are vaguely humanoid, with a head, two eyes, two arms, two legs.

|

| Clover (from Cloverfield) |

|

| Rancor (from Star Wars: Return of the Jedi) |

|

| Frank (from Donnie Darko) |

|

| The Giant Behemoth (1959) |

|

| Xenomorph (from Alien) |

Which took me to cryptids. Many are humanoid, like Mothman and Sasquatch, but some are not. From LOLWOT: the Mongolian Death Worm, Rocs, the Mokele-Mbembe, the Jersey Devil, and El Chupacabra. Oh, and Nessie, of course.

|

| Mongolian Death Worm |

|

| Mokele-Mbembe |

|

| The Jersey Devil |

|

| El Chupacabra |

It’s striking that most of even the non-humanoid ones have anthropomorphic features, like pairs of arms, legs, and eyes. Fenrir and the Chupacabra are mammals. Ramiel in Neon Genesis Evangelion is the exception that proves the rule, with the Dire Serpents as the transition case. Anthropomorphism is hard to shake!

The Uncanny Valley

The range of movie monsters from almost-human to completely abstract took me to the uncanny valley. Robot designers want to avoid it since they want us to warm to their creations. But monster makers might seek it out since it’s the place where these entities will be most creepy.

Aside: some alternatives to “uncanny valley”: creepy canyon, hollow of horror, ghastly chasm, eerie gully, loathsome lowland. And that's even before asking an LLM.

Serpents and dragons in the western tradition are the prototypical denizens of the ghastly chasm, being neither humanoid nor abstract. It’s disappointing that so many monsters don’t fit that archetype, undermining my uncanny valley argument.

David Jones’ An Instinct for Dragons had a big influence on me twenty years ago. He proposed that the dragon archetype is based on three main predators that posed significant threats to early primates: raptors (birds of prey); big cats like leopards; and reptiles like pythons. I distinctly remember that he argued that the fire-breathing dragons was rooted in carnivores’ bad breath due to rotting meat stuck between their teeth. A lovely book.

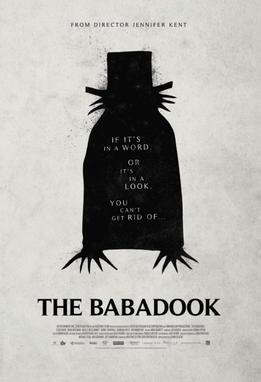

Still, many monster tropes try to shift monsters away from the human, e.g. “faceless bureaucrats” (implying that they’re all the more dreadful because they could, but don’t, have faces). Other faceless antagonists include The Blob (1958 movie), John Carpenter's The Thing, The Babadook (2014 film), and The Demogorgon from Stranger Things.

No comments:

Post a Comment