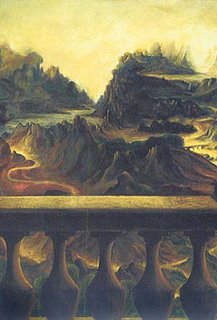

Sophie Mattisse’s paintings look familiar, but can be hard to place – until one realizes that they are famous works from which the people have been removed. I heard about her work in a piece (MP3) on the Studio 360 radio show. (Read more in an artnet article; the Feigen gallery has more images.)

Sophie Mattisse’s paintings look familiar, but can be hard to place – until one realizes that they are famous works from which the people have been removed. I heard about her work in a piece (MP3) on the Studio 360 radio show. (Read more in an artnet article; the Feigen gallery has more images.) It led me to think about what text would be like, stripped of people.

Here are the first two chapters of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, with the dialog removed:

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.

However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a neighbourhood, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered as the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.

Mr. Bennet was among the earliest of those who waited on Mr. Bingley. He had always intended to visit him, though to the last always assuring his wife that he should not go; and till the evening after the visit was paid, she had no knowledge of it. It was then disclosed in the following manner.

Mrs. Bennet deigned not to make any reply; but unable to contain herself, began scolding one of her daughters.

Mary wished to say something very sensible, but knew not how.

This is not quite the same as Matisse’s work, since references to people remain. If one keeps only sentences which don’t refer to people, very little remains. Here are the first five chapters, so abridged:

It was then disclosed in the following manner.

Nothing could be more delightful!

Such amiable qualities must speak for themselves.

The distinction had perhaps been felt too strongly.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a very different book; much remains of the first few pages when references to people are removed. This kind of excision is a way to characterize a novel. Little will remain for novelists who are concerned with people; much will remain for those concerned with setting.

The Nellie, a cruising yawl, swung to her anchor without a flutter of the sails, and was at rest. The flood had made, the wind was nearly calm, and being bound down the river, the only thing for it was to come to and wait for the turn of the tide.

The sea-reach of the

Afterwards there was silence on board the yacht.

The day was ending in a serenity of still and exquisite brilliance. The water shone pacifically; the sky, without a speck, was a benign immensity of unstained light; the very mist on the

Forthwith a change came over the waters, and the serenity became less brilliant but more profound. The old river in its broad reach rested unruffled at the decline of day, after ages of good service done to the race that peopled its banks, spread out in the tranquil dignity of a waterway leading to the uttermost ends of the earth.

This exercise set me wondering: What would be left if one drained the venom from political speech? This is harder to do; what should be cut? Only personal attacks and sarcasm, or snide remarks and irony, too?

I tried it out on 'Chocolate City' Sprinkled With Nuts, picked at random from the Ann Coulter archive on townhall.com, by keeping only what seemed to be factual statements. The original 807 words boiled down to these 81:

So Hillary Clinton thinks the House of Representatives is being "run like a plantation." And, she added, "you know what I'm talking about."

As Hillary explained, the House "has been run in a way so that nobody with a contrary view has had a chance to present legislation, to make an argument, to be heard."

His mother immediately told the press, "Of course he's against abortion."

He had expressed support for the Reagan administration's positions on abortion in a 1985 memo.

No, taking out the ad hominem takes out all the fun – which can’t, thankfully, be said for Sophie Matisse’s work.